During student teaching I watched Mr. Gustkey, my host teacher, gives students one goal in his language arts class: To become better writers and thinkers by the end of the year. But how does Mr. Gustkey know if his students are better writers and thinkers at the end of the year? Classroom assessments serve as meaningful sources of information for teachers, helping them identify what they taught well and what they need to work on (Guskey, 2003). A classroom assessment can take many forms. It can look like a journal entry, a written test, or a verbal spelling game.

Assessment helps students to do their best work. Teachers support learning by giving students feedback on their learning progress and by helping them recognize learning problems (Bloom, Madaus, & Hastings, 1981). I believe in allowing students multiple attempts on assessment. All writing teachers know the benefits of a second chance. They know that students rarely write their best on a first draft. Teachers build into the writing process opportunities for students to gain feedback and to revise and improve their writing.

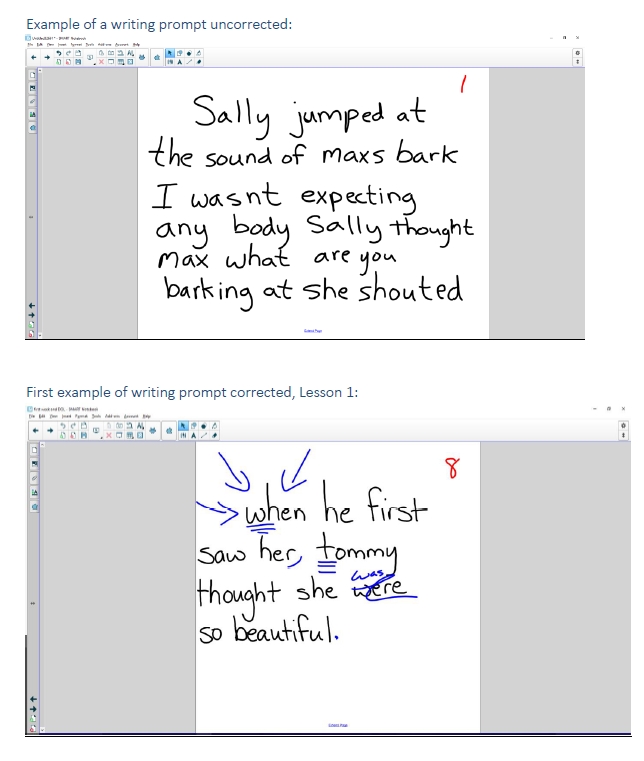

Included in my portfolio is a teacher work sample that describes a punctuation assessment delivered to all students in Mr. Gustkey’s 7th grade class. We assessed students early in the semester and developed lessons to correct mistakes in punctuation, such as appropriate usage of quotation marks and commas. It was exciting to see the student grow after these interventions. 14 out of 18 (77%) students improved their scores, and the girls outscored the boys with a 27% overall learning gain score. All students were happy with their improvement and it led to me feeling like I was being an effective teacher.

And that’s what effective teachers do, isn’t it? They adjust their teaching to serve the students they are working with. They understand the principle that all people can learn under the right conditions, and that carries an important implication. Fantini (1986) describes it well: “If a program does not achieve the intended goals. Then it is redesigned until it does. There are no learner failures only program failures.” (Fantini, 1986)

References

Bloom, B. S., Madaus, G. F., & Hastings, J. T. (1981). Evaluation to improve learning. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fantini, M. D. (1986). Regaining excellence in education. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Guskey, T. (2003). How Classroom Assessments Improve Learning. Educational Leadership, 60(5), 6-11. Retrieved July 10, 2018, from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/feb03/vol60/num05/How-Classroom-Assessments-Improve-Learning.aspx

Heppen, J. et al. (2010, December). Using Data to Improve Instruction in the Great City Schools: Key Dimensions of Practice. Washington, DC: Council of the Great City Schools

Larocque, M. (2007) Closing the Achievement Gap: The Experience of a Middle School. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 80:4, 157-162, DOI: 10.3200/TCHS.80.4.157-162

Wiggins, G. (1998). Educative assessment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.