I expect that most readers of this portfolio to understand and appreciate the importance of arts education. Judging by nationwide budget cuts to school music, theatre, and dance programs, (Mahnken, 2017) I have deduced that most policymakers do not value the arts. It makes me sad as an artist and as an educator that children may miss out on everything that arts training brought to my life. It brought me excitement, community, purpose and the ability to honestly express myself. I know that being in a high school musical changed my life, and brain research has found that the arts develop more than just expressive and affective skills (Sousa, 2006). They also develop deeply cognitive structures:

The arts develop essential thinking tools — pattern recognition and development; mental representations of what is observed or imagined; symbolic, allegorical and metaphorical representations; careful observation of the world; and abstraction from complexity (Sousa, 2006).

In these days of increased scrutiny of public education spending, arts educators must publish scientific justification for using school time to rehearse a play. Did you know that when students dramatically reenacted a story, their comprehension of the story improved? Researchers found the effects were greatest for first graders who were reading below grade level (Ruppert, 2006). If politicians or taxpayers need a research study to convince them that kids should practice painting or play instruments, then we can get them one.

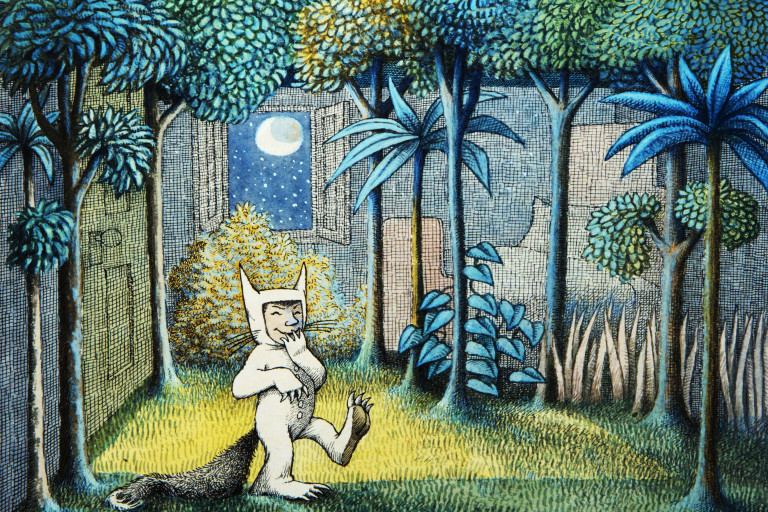

My portfolio includes a Where the Wild Things Are integrated unit that invites students into the world of dance. By combining a beloved picture book with imaginative masks and choreography, teachers can introduce their 1st grade class the basics of dramatic acting and interpretive dance. The positive effects of dance education are powerful and enduring, with considerable evidence proving the value of embodied learning. In schools where dance programs flourish, students’ attendance rises, teachers are more satisfied, and the overall sense of community grows. (Bonbright, Bradley & Dooling, 2013)

Readers of this portfolio don’t need research studies to know that integrating the arts with core subjects allows for sustained attention and motivation, providing an increased opportunity for the training to be effective (Posner, Rothbart, Sheese & Kieras, 2008). Integrating arts should always be done with intention, but it need not be complicated. First find a theme to your lesson and highlight the material that requires deep thought or would be important to remember. Then lead an art project that allows students to explore the material in a deeper way.

Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (1984) is a profound and delightful story that deserves deeper exploration. With the attached unit, 6 and 7-year-olds will be able to imagine and dance in a world of friendly monsters, sail boats, and wild rumpuses. Can you imagine the silly masks and movements that the students will dream up? I can. I don’t understand why we need research studies and neuroscience to justify it, but I hope that the facts and figures I’ve included make a strong case.

References

Bonbright, J., Bradley, K., Dooling, S. (2013, July). A Report on the Impact of Dance in the K- 12 Setting. Retrieved from National Dance Education Organization website: http://www.ndeo.org/

Sousa, D. (2006). How the Arts Develop the Young Brain. Retrieved July 7, 2018, from http://www.aasa.org/SchoolAdministratorArticle.aspx?id=7378

Posner, M., Rothbart, M. K., Sheese, B. E., & Kieras, J. (2008, March). Arts and Cognition Monograph: How Arts Training Influences Cognition. Retrieved July 7, 2018, from http://www.dana.org/Publications/ReportDetails.aspx?id=44253

Ruppert, S. (2006). Critical evidence: How the arts benefit student achievement. Retrieved March 31, 2013, from National Association of State Arts Agencies:

http://nasaa-arts.org/Research/Key-Topics/Arts-Education/criticalevidence.pdf

Sendak, M. (1984). Where the wild things are. New York: Harper & Row.